As a professor of early American Literature, I read a lot, but mostly DWG (Dead White Guy) Lit. In the good old Colonial days (fun times!), native stories were rarely recorded, it was illegal to teach slaves to read and write, and women were discouraged from engaging in such frivolous activities. Even white guys couldn’t get anything published unless it was religious, historical (e.g. diaries) promotional, or occasional, and the few women who broke through such barriers were especially limited, which is why I always wonder what Ann Bradstreet and the remarkable Phyllis Wheatley could have done if they had the intellectual freedom of a Shakespeare. That all changed, of course, as the Puritans fell out of power, but even then, most of the DWG Lit, while important (I’m thinking of Jefferson, Paine, deCrevecoeur) was, let’s face it, pretty dry. (Have you read Franklin’s Autobiography all the way through? God help you.) It takes a couple of centuries for our national literature to get interesting—that’s when the slave narratives and novels (by both men and women) kick in, and the short-story form blossoms. (The drama and poetry—excepting Whitman and Dickinson—are still generally awful until the late 19th century.) And when I teach these works, no matter how many times I’ve done it before, I need to re-read them.

Thus reading, while always enjoyable (I recently re-read Moby-Dick for the ninth time and was thrilled anew by the power of Melville’s prose), has, by and large, turned into something of a chore. And that’s just weird for me. I grew up a dweeby, four-eyed bibliophile. I read in bed (under the covers, by flashlight), on the living-room floor, on the porch, on the front steps, in the back seat of my parents’ car, in the branches of the dogwood tree. I read while dribbling a basketball. So naturally, when I went to college, I became an English major, and ever since then—for the last thirty years—reading has been more requirement than pleasure.

Thus it is with great excitement that I greet the arrival of April, because that is when (my spring semester drawing to an end, and summer classes all prepared for) I can relax, pick up a book, and read for the sheer joy of it.

Last summer I dove into about twenty books, including five of the best story collections I’ve ever read in my life: Amina Gautier’s At-Risk, Midge Raymond’s Forgetting English, Anthony Doerr’s The Shell Collector, George Saunders’ 10th of December, and Lori Ostlund’s The Bigness of the World. And some very good novels: Kent Haruf’s Plainsong, Allen Learst’s Dancing at the Gold Monkey, Alice Laplante’s Turn of Mind, Jennifer Egan’s A Visit from the Goon Squad, Judy Doenges’ The Most Beautiful Girl in the World, Sophfronia Scott’s All I Need to Get By, and (to privately commemorate his passing) Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude. Delightful reading all around.

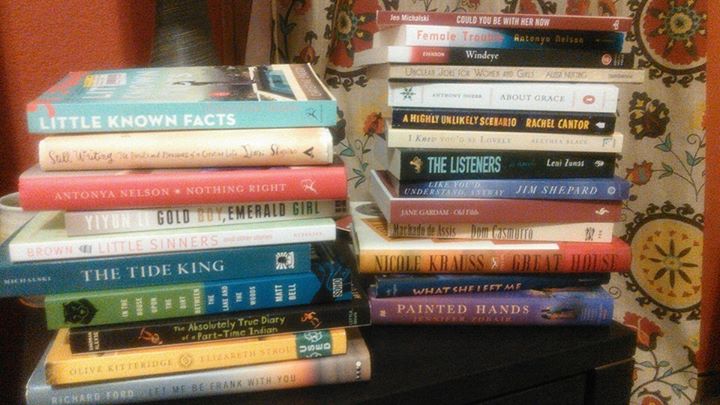

This year, I’ve got my reading all lined up–or rather piled up, on my nightstand, and I’m sure to add to this stack when I’m at the AWP conference next week:

(Not pictured: Cari Luna’s The Revolution of Every Day, which for some reason is at my office.)

I may throw in a classic or two (I’m thinking it’s high time I re-read Dostoevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov), and I may also revisit some of my favorite books of the last thirty years (Nicole Kraus’s A History of Love and Ron Carlson’s Plan B for the Middle Class come to mind), but mostly I’ll spend the late spring and all of the summer reading new books, or books that were fairly new when I bought them but it’s taken me years to get to (because I spend August to April reading or re-reading in the 19th century).

The pleasure I get from reading my contemporaries derives mostly from my knowledge that these authors are alive and vibrant. Even as I’m reading their words, they are writing new words. They haven’t yet (with the exception of such giants as Morrison, McCarthy, and Pynchon) become icons I would feel intimidated by, authors whose writing is so majestic that I can’t help but feel inadequate after finishing their books.

But knowing my contemporaries are out there, alive and working, also has its drawbacks—especially if I know them personally or am social-media friends with them. What if I don’t like their books? Thrice last summer I had the experience of buying a book written by a friend or acquaintance, only to find that I hated it—or at least considered it terribly uneven or just okay—and then had to come up with something to say about it. The books had already been published, so I couldn’t offer any sage revision advice, and I had already notified them I was reading it, or put it on my “Currently Reading” list on Goodreads (a telegram of sorts, with the implication that I would probably review it positively). I’ve since learned (after buying a much-acclaimed new novel written by a well-known acquaintance of mine, reading the first six overwrought pages, then throwing the book across the room) not to announce anything I’m reading on Goodreads until I’ve at least started it and am enjoying it—unless the writer is either dead or so famous she couldn’t possibly care what a nobody like me would think of her masterpiece.

But this summer, I think I’ll just skip the reviewing, since my real objectives are (1) to enjoy a good read, (2) feel connected to the current writing scene, and (3) to learn from what and how others are writing. Because every time I read a good book, I become a better writer.

And every time I read a good book—for pleasure, not for my job—I return to the happiness of my youth.

What books are on your nightstand? Take a picture of your stack and share it in the Comments Section below.

![]()

Leave A Comment