My father died six and a half years ago.

At first, right afterward, he was “around.” Hovering, I guess you could call it: at the foot of my bed; in the car, making sure I drove safely; listening to my phone conversations as I told my friends of my ambivalence about his legacy—yes, he was a sweet father in his later years, but when I was young, when I needed him most, he could be aloof, an uneasy communicator, unable to give me what I needed. In retrospect, I think in these phone conversations I was trying to figure out how I felt; I didn’t want to fall back on platitudes and simplistic assessments, so I went to my comfort zone, which was . . . confused.

He was my father, right? This was complicated.

Then, after I’d hang up: Damn. Pop, were you listening to that?

In the car, on my way to work, I’d address him out loud. Listen, here’s the truth: I’m an ungrateful shit. You were busy and stressed when I was young, trying to provide for all of us, but you still showed up—for everything. Thank you for that. And thanks for taking on those crap jobs just so we could have a safe and stable home. And thanks for putting up with all the stupid stuff I did—coming home at 5:30 in the morning, putting a gash in your car without knowing how it got there, calling you fat when you weren’t, missing my train stops and phoning you after midnight to pick me up . . . my god, the list is endless. Thank you for everything. I’m sorry I badmouthed you.

I went back and forth like that, criticizing and apologizing, for weeks.

He probably wasn’t listening anyway. He seemed to be spending most of his purgatorial time with my mother. He had once told her that when he kicked the bucket, he wanted his ashes put on their bedroom dresser, so he could keep an eye on her. She would have nothing of it—when he died and was cremated, she put his ashes directly into the ground, in a dual plot they had purchased at a nearby cemetery—but as it turns out, he didn’t need to be there, physically, on their dresser. He came to her in her dreams. He whispered to her at night, when she was alone. He stroked her forehead, invisibly. In a photograph taken of my mother shortly after his death, she is sitting on the couch with her friends, and there is a bright circle of light on the wall behind her—perfectly round, the size of a dinner plate. There was no flash; there was nothing shiny on the wall; there is no plausible explanation for that light. Except one.

Then, four or five weeks later, while I was still trying to work through my feelings while pretending I was fine, he was gone. Really gone. No feeling that he was watching me, no more conversations in the car. Gone. So I did the guy thing: I went about my business. I’d be jarred back into an awareness of his absence only at odd, increasingly sporadic moments, like when the phone would ring and I’d intuitively think it was him: Dav! How’s my boy? Did you see the game Carmelo had last night? (He called me “Dahv” because my mother is Italian, and in Italian my name is Davide or Davidino—so Dav for short.) Or when I’d arrive at Laguardia Airport and walk outside, expecting to see him curbside in his Chevy Impala, with a bottle of water waiting for me. Or when my mother would call, her voice choked and milky, trying to tell me what it was like, to sleep in the empty bed she had shared for fifty-one years with the only man she ever loved, to wake up reaching for him only to find him gone.

For her, still pretty and energetic and a long way from elderly (she was only seventeen when they married), the loss was seemingly irreparable, a rent in the fabric of her life, of her identity. But even for her, the passage of time since–over six years–has allowed for an abatement of grief, a gradual diminishment of pain, just as it had when she lost her daughter, my sister Sandra, decades earlier. What feels permanent and inconsolable, it seems, eventually becomes bearable, then manageable, until it’s absorbed into your skin, and finally into your cells, evolving from an alien intrusion you battle every day to an accepted part of your psychological DNA.

So: what lives on, now that he’s truly gone?

Images.

Feeling the touch of his hand as he pet the back of my head—both a sign of affection and a reminder that my hair was too long.

Smelling his maroon windbreaker—a combination of cigarette smoke and Aramis, his deodorant.

An earlier smell—of Vitalis, which he used to slick back his hair. (As a boy, I would open the bottle, sniff it, and sneak a drop into my own hair.)

Flinching at his voice when he was angry—a sharp bark that sat me up straight in my dining-room chair.

Walking into the living room and seeing him in the armchair, feet up, mouth open, snoring.

Seeing him outside in the humidity with an old white tee-shirt on, painting the front steps, or building a deck outside the back door, or re-chaining my bike—bullets of sweat on his forehead, the tip of his tongue sticking out from his lips.

Feeling his shoulders, wet and strong, as I rode his back in the Brentwood pool; he’d make a funny dolphin sound, pursing his lips at the surface of the water, then glide underwater with me clinging to his neck and holding my breath.

Watching him during mass, after Communion, as he went to the rear of the church, picked up one of the long-handled baskets, walked to the front and came back down toward me, row by row, accepting donations with a thin, polite smile. (It was something he did voluntarily, out of a sense of duty, but for years I thought it was because he was an important man in the community, selected by God–or by the bishop at least–to collect everyone’s money.)

Hearing his trademark whistle—two short, sharp chirps—from the darkened auditorium just before my concert was to begin, or from the stands in the gymnasium when I was about to take a foul shot: I’m here. Or down the block as I rode my bike with my brother or played with my friends: Time to come home.

Studying his face as he drove me home from my basketball games, awaiting his critique of what I had done wrong in the fourth quarter.

Watching him chop up a head of iceberg lettuce and mix in a container of cottage cheese and a can of Dole pineapples—embarrassed perhaps that this was our dinner, but cheerfully telling us we were in for a treat.

Seeing him in his office, with a brown sports jacket and striped tie, introducing me to his workmates, his hand on my shoulder.

Feeling the “cheese” on his forearms—lumps under his skin, fatty deposits that made his arms look like the surface of the moon.

Seeing him come out the back door to shoot baskets with me, just for a few minutes—his leaning, arc-less jump shot, his quick hook shot, jabbing his elbow into my ribs as I tried to defend him.

Sitting on the couch, watching “True Grit,” or “Shane,” or “The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly” or “The Outlaw Josie Wales” or “Jeremiah Johnson” or “The Dirty Dozen.”

Listening to an Andrea Boccelli song at full volume, with him smiling, his hands out, as if conducting.

Attempting to hug him, only to have him gently punch me in the ribs.

Seeing his face when he came to my door one day, when I was an adult, living in Yonkers—troubled, exasperated, frustrated, drained.

Tiptoeing into the kitchen when he came home from work and watching him kiss my mother.

Seeing him in one of the armchairs arranged in a circle at the medical center, one affable man among seven or eight, all of them hooked up to dialysis machines and watching television, their blood vessels being emptied, cleaned, and filled again.

Imagining him in that chair, hopefully sound asleep, when the massive heart attack came.

Words.

After telling him about a girl I had a crush on: “Really? She’s such a dog.”

On car trips, when I asked him where we were going. “Cos Cob.” (We never, of course, went to Cos Cob. He just found the name amusing.)

After one of us (usually me) spilled the milk, or otherwise made a mess, at the dinner table: “Well, you win the Slobbo of the Day award.”

After one of my sarcastic friends left our house: “So you like making fun of other people? What makes you so special that you can laugh at others?”

After watching a news story about a young woman who had volunteered to help the poor in some remote country, and while there, had been killed: “Now that girl? She’s a hero. That’s who you should be like.”

When I (at age nine) sang along perfectly to a Jackson Five song: “Shut up, you sound like a girl.”

When he was coaching basketball, as soon as somebody rebounded the ball, pointing downcourt: “Look down! Look down!”

When I told him I was getting a divorce: “I’m disappointed in you.”

The last time I saw him, on our visit during Christmas break, 2006: “I’m proud of you, son.”

And then, when I was leaving: “Love you, Dav.”

Memories.

In the front of the car, when he was in a good mood and we were going to the beach, he’d smack my mother’s bare thigh, sometimes hard. “Sam!” she’d say, and a wide red splotch would appear on her leg. (I never knew what to think; it seemed mean, but it also meant he was happy.)

While I was lying on the floor, watching television, he occasionally gave me a “Charlie horse”—a sharp punch in the thigh, just under my quadriceps. My mother would yell at him for hurting me, but he’d just chuckle and say he was just “toughing me up.”

When my brother and I were young, and we misbehaved, he gave us a choice: no television for a week, or a bare-bottom spanking. I’d weigh my options, talk it over with Steve, and every time, the prospect of missing my favorite sporting events or TV shows (The Courtship of Eddie’s Father, Julia, The Flip Wilson Show, Laugh-in, The Carol Burnett Show, Adam-12) would seem more tragic than the intense but ultimately fleeting pain of the bare-bottom spanking. But then, after years of opting for the spanking, one day, when I was ten or so, he bent me over his knee as I covered my eyes, bracing for the wallop; but nothing came. He pushed me off and told me to go to my room. “It hurts me more than it hurts you,” he said.

Once, Steve said something rude, or did something wrong—for the life of me, I can’t remember what it was, but it was probably something disrespectful to my mother—and my father stood up and hit him. We were all silent after that.

When he took us to the hospital after my second sister was born (she weighed less than two pounds, and my mother nearly died from hemorrhaging), my father went inside, as my brother and I sat in the car in the parking lot and waited for him to get to my mother’s room, and for my mother to appear at the window—a wispy figure in white, weakly waving.

When I was fourteen or fifteen, and my mother went to Italy without us, I made breakfast for my father—scrambled eggs, or French toast with a little cinnamon. Watching him eat what I cooked for him was the beginning of a lifelong pleasure: cooking for people I love.

When lying on the floor watching television, he would get me in a “scissor grip,” putting my skinny body between his legs, crossing his ankles, and squeezing tight. There was no way of getting out, even though I tried, mightily, each time.

A few times when I visited for the weekend, he’d ask me to join him for his Friday Morning Breakfast at the Mamaroneck Diner with his old high-school buddies. When the coffee came, they all took out their pills and complained about their latest medical procedures. They would tease the waitress when she started to tell them all what they were going to order, but then they would order it anyway.

His favorite way to wake me up (when I slept late as a teenager) was to grab hold of my big toe and twist it. In our very last conversation, he said that when he died, he was going to try to twist my toe from the afterworld, so I should leave one foot outside the covers at all times. (I did, night after night. Come on, Pop. You can do it.)

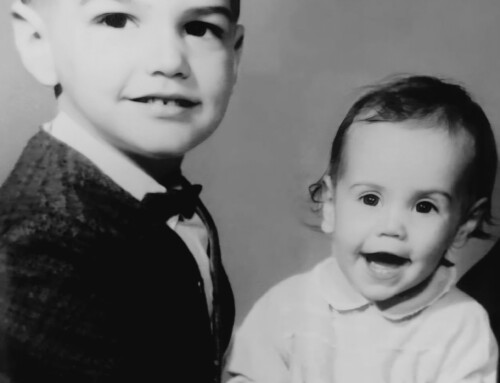

In my earliest memory, I am sitting high upon my father’s shoulders as he walks down the upstairs hallway. My head is bobbing near the ceiling. He is taking me into his bedroom, singing my favorite song (and, unbeknownst to me, changing the lyrics). His voice is high and sweet:

My boy lollipop / Isn’t he a dandy / My boy lollipop / He’s sweet as candy

Right after I duck to get through the doorway, he launches me through the air—a delirious, suspended moment. I land on his big bed, giggling, hoping he won’t tickle-attack me. Hoping he will.

After his death, my brother and I went through some of his belongings, and we found, in his wallet, three lottery tickets. One of us noticed that the numbers on the tickets were the birthdates of his three surviving children. I guessed at his intentions: whoever’s birthday numbers won, that child would get the money. Or, if it was a big jackpot, he’d divide the winnings among all three of us. Actually if it was a really big jackpot, he’d give thousands of dollars to everyone in the family, and probably to some friends, some neighbors, the old waitress at the diner . . . One thing we knew for sure: he wouldn’t have kept it for himself.

Until that moment, I had been sad, but I was keeping it together. Just weeks earlier, Cynthia and I had visited, and my father and I (when we were alone and my mother couldn’t hear us), had talked about the prospect of his death. He seemed to have come to terms with it: he had lived a good life, his children and grandchildren were all set up and doing well, and except for the prospect of missing my mom and knowing she’d be sad, he was comfortable with the idea of it—excited, even, at the prospect of seeing his daughter and brother again. At the end, we hugged. I told him he’d been a great dad, and that I loved him very much. So when he suddenly died a few weeks later, I felt comforted in knowing that we had had this time together; I had said what I wanted to say.

But when I saw those lottery tickets, I lost it. But I was crying for him, not for myself. The man was a martyr; he never did anything for himself. Those lottery tickets, like the 30-year-old blueprint in his dresser drawer for his dream house on Cape Cod, were symbols of a dream deferred, of a life unlived–or only partially lived. After all, if you’re happy with your life, truly happy, is there any need to buy a lottery ticket, or draw up plans for a dream house? My father’s passivity, his inability to do what he wanted to do, meant that he was always there for us, yes, but it also meant that he presented himself daily as a role model of someone who rarely did what he wanted to do. And as an adult, I dutifully followed his example, living wholly for others, until I couldn’t do it anymore—and that’s when I became, for a two-year period anyway, remarkably selfish.

But (I thought, while my brother and I looked through newspapers to see if he had, on the day of his death, finally won the lottery), who was I to judge him, when he himself had told me, hand on heart, that he was happy, that his life was complete? What standards was I applying to his life? He was no member of the “Oprah generation,” bent on self-awareness and self-gratification. He was of the Greatest Generation, born during the Great Depression and raised on the belief that if you could provide a better life for your children than the one you had, then your life would be a success. And here he was, a high-school grad, with one son a successful lawyer, universally repected and liked; another a professor; and a daughter who was a champion teacher and accomplished athlete–all with advanced degrees, all with loving spouses or partners, all with beautiful children. His life, therefore, was irrefutably a success, his selflessness (or passivity, as I had been seeing it) justified and rewarded. If anything, I thought, I should be grateful, not critical. And feeling sorry for him? He would find that ridiculous. The man had everything he had ever wanted.

I put my head in my hands, as if to hide my tears; but in reality, I felt ashamed.

Upstairs, in his filing cabinet in the attic, we found the obituary he had written for himself:

Richard Samuel Hicks of Harrison, NY. Died January 26, 2007 at age 74. Born August 20, 1932 in Harrison to James and Frances (Bray) Hicks. He served in the Navy and while stationed in Italy he met his wife of 51 years Albina Magliulo. He started his career as a computer programmer for Homelite in Port Chester and then Sealectro in Mamaroneck. He later owned Sam’s Deli in Ardsley and most recently a security guard at the Springs in Purchase. Richard was the Past President of the Holy Name Society and a former Basketball Coach for St. Gregory’s Parish and a Troop Leader for the Boy Scouts of America. Survived by his wife Albina, children Stephen (wife Mandy), David (wife Cynthia), Marisa (husband Roger) Horvath, grandchildren Samantha, Christopher, Stephen, Caitlin, and Roger Jr., a brother Robert (wife Maureen) and sister-in-law Mary Hicks. Predeceased by a daughter Sandra Hicks, and a brother Roger. His children and grandchildren were his life.

Damn straight. For Richard Samuel Hicks, life was an Either/Or proposition—either you devoted it to others (your family, your country, your church, your community), or you lived it in a hedonistic, self-absorbed manner—and his choice, to make his children and grandchildren his life, had made all the difference for him. It’s not the choice I wound up making, even though I started out that way–I now believe it’s possible to balance the two, to wed self-sacrifice and self-fulfillment, to both tend to those I love and pursue my own passions–but since I screwed up my life and my father never did, my job, as I now see it, is to not to scold him posthumously for not living the way I think he should have lived, but to respect his worldview, to honor his decision, to understand how I benefitted from it, and to learn from his example.

And to show some gratitude, for crying out loud.

So: Thanks, Pop. For everything. I now know that the best part of me is the part of me that’s like you.

P.S. How’s Cos Cob?

![]()