[This essay was first presented on the “Life And . . . ” Podcast in April 2022.]

I’ve always had a hard time with celebrations.

I grew up in a working-class household near the Bronx. My parents were born during the Great Depression, and we lost my sister when I was five; so . . .birthdays, job promotions, weddings, getting A’s on tests, all the kinds of events that typically call for celebration– were modest affairs, somewhat muted, you could say, and tinged with sadness over the empty chair in the room. One Christmas, the ultimate celebration, my brother and I woke up and came downstairs, excited to see all the red-and-gold-wrapped presents under the tree, but my parents were sitting in the corner, sobbing, hit by a sudden wave of grief.

So I grew up quiet. I read books in my room, or at the local library, or on the back stoop. My kind, goodhearted parents instilled in me the values of modesty and humility, to think of others more than myself. Any accomplishment was appreciated, certainly. But not . . . celebrated. Celebrations were the equivalent of boasting, “making a show of yourself.”

My brother and I were the first in our family to go to college, and in my freshman year, I remember being assigned Walt Whitman’s “Song of Myself,” which begins,

I celebrate myself, and sing myself,

And what I assume you shall assume,

For every atom belonging to me as good belongs to you.

Well that’s pretty cocky, I thought. Here was this dude, just loafing on the grass, celebrating . . . not the accomplishments of others, or a public event, but . . . .Himself! His mind, his words, his spirit, but also his body–especially his body. “The scent of my armpits,” he says at one point, is an “aroma finer than prayer.”

Get outta here, Walt Whitman I thought, and I shut the book.

Without realizing how much I sounded like my father.

Years later, in graduate school, I returned to Whitman, and had a completely different reaction. Wow, I thought. If only. If only I could write with such confidence! If only I could celebrate my self like this, even just a little bit. I recalled, as a toddler, bringing my stinky feet to my nose, or sniffing my armpits at the onset of puberty, and I understood that what Whitman was advocating was a return to our nature. He wasn’t simply appreciating the natural beauty and sexuality that our parents, teachers, religious leaders and . . . well everyone teaches us to be ashamed of; he was boasting of it, celebrating it, publicly. I learned that he had self-published his book—another form of celebration–, and had anonymously reviewed it, in a celebratory manner—“An American bard at last!” he wrote of himself—and then he had the impudence to sell copies of it on the streets of New York!

And just like that, Whitman was cool. I mean, this was the mid-19th century. Talk about uptight! But in spite of the criticism he received for being so . . . egocentric and brazen and . . . “bestial,” he knew he had worked hard to compose his beautiful and daring poetry, and he was determined to celebrate it, and himself.

I remember walking to church one day with my family, all dressed up—it was probably Easter Sunday, and I was six or seven years old. “My handsome boy,” my mother had called me when she had combed my hair for me. But when we walked past a store window and I paused to check myself out in its reflection, she tugged on my arm. “Don’t be vain,” she said.

This is probably why I ended up working so many blue-collar jobs—sanitation worker, landscaper, dishwasher, busboy, waiter—and working my way through school to become a , teacher, always in service of others, while never once considering doing what I really wanted to do, which was to be a writer. But after a decade or so teaching, I started to feel that old calling, more and more. Instead of talking about writers in class, I wanted to be a writer. Instead of talking about books, I wanted to write my own book. So I started going to readings at the 92nd Street Y, took some creative writing workshops, and finally, in my early forties, after writing a short story and revising it at least fifty times, I sent it to my favorite magazine, Glimmer Train.

Two weeks later, to my amazement, I received a call from one of the editors, congratulating me; they loved my story and had decided to publish it.

Woo-hoo! Time to celebrate, right?

I couldn’t.

I should call someone, I thought. But that would be bragging.

Finally, I called my friend Lauree, a life coach who had been encouraging me to shift my identity from a professor who occasionally wrote to a writer who occasionally professed. “Oh my god!” she said, “How cool! You need to celebrate this.”

When I fell silent, certain that I would not be celebrating this—I had no idea how to celebrate this—she challenged me. “David. Tell me right now how you’re going to celebrate this.”

I muttered something about having a beer with friends, but she didn’t buy it. So I said I needed to think about it, I’d get back to her. But by the time I hung up, she and I both knew it wasn’t going to happen.

Nearly two years later, when the issue finally came out, I opened it with pride. On the cover was an illustration based on my story! And my story, called “Spring Creek Pass,” was the first of the issue, and on the page before it, in the Glimmer Train tradition, was a childhood picture I had sent them, of three-year-old me, sitting with my brother and sister. I thought, she would be so proud of me.

Then I shut the magazine and put it on the shelf.

The year after that story was published, I married the love of my life, and as a Christmas gift, she had that Glimmer Train magazine cover and the first page of my story professionally matted and framed, side by side. When I opened the gift and saw the cover on the left side—depicting a hawk flying over a river gorge, with the snow-covered Rockies in the background—and the first page of my story on the right, with the title and my signature at the top– I was speechless. It was something I would never have thought of doing, and yet, if I had any degree of confidence, that’s exactly how I would have celebrated that accomplishment: by framing it and hanging it on the wall for me to see, every day.

My wife was celebrating me.

Fast-forward ten years: I’d published more autobiographical stories, and arranged them sequentially as chapters of a novel, called White Plains. I’d found an agent, and I had a book contract with a small press called Conundrum, which, like most small presses, had no budget for the promotion, also known as the celebration, of my book. I was now fifty-six years old. Late to the game. I hadn’t celebrated the agent contract or the book contract. Surely I should celebrate its publication, right?

For years, as a professor, writing workshop instructor, and then as director of an MFA program, I had been telling new writers they need to learn how to promote themselves. That publishers aren’t paying for book tours anymore. Why, I would ask the students, did you work so hard to write and revise this book, if not so that people could read it? And how can anyone read your book if they don’t even know it exists? You have to promote it yourself. You have to celebrate yourself.

Now here I was with my own book release coming up. And who knew? It could be the only book I ever published, right?

So, I decided to do it. To go all-out. To beat down that inner voice reminding me to be modest, telling me not to brag. To celebrate my book, in other words. To celebrate myself. To sing myself, even, as Whitman put it.

I planned a 50-stop book tour, with readings all across the country. And in the spirit of Whitman–“every atom belonging to me as good belongs to you,” –at almost every stop, I planned on reading with another writer or two from that city—a communal event. And I would invite everyone I knew in that city—friends, former students, high-school or college buddies—and even some I didn’t know, and afterwards we’d all go out for a beer.

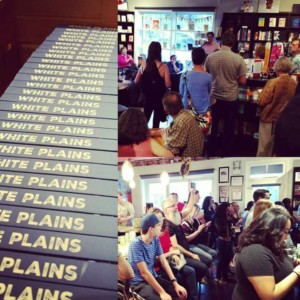

At the launch, at the Bookbar in Denver, I was terrified that nobody would show up. But at least sixty people were there, cramming into the little store, smiling and lining up to buy books.

But before I even got there, before I entered the store and embraced my friends, gave a brief reading, ate two slices of cake with a sugary imprint of my book cover on it, before I drank champagne and signed a lot of books, I had already felt sufficiently celebrated. Because on our way there, my wife and children and I had stopped for dinner, and as I sat with them, the four of us laughing and enjoying each other’s company, out of nowhere, I felt it. This is it, right here. We’re celebrating. Together. Because we did this together. My wife had edited the book, several times, brilliantly. My kids had contributed two moving chapters from their childhood points of view. This was our book. And we were about to launch it together.

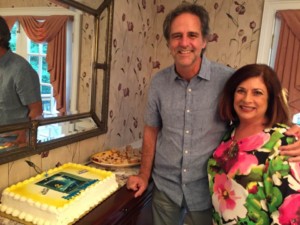

On that epic and oh-so-much-fun book tour, there were several kinds of celebrations, but most were celebrations of friendship—reading with a former housemate in Austin; visiting a book club of twenty-five women hosted by my former babysitter, who had an enormous birthday cake waiting for me; reading at a pub in Rochester with college friends I hadn’t seen in thirty-five years; and a stop at a Binghamton diner, for a big breakfast with some old friends, that unexpectedly turned into a celebration when they brought their families and friends with them, took over an entire section of the diner, and made me go out to my car to bring in a box of books for them to buy—a joyous celebration if there ever was one.

On that epic and oh-so-much-fun book tour, there were several kinds of celebrations, but most were celebrations of friendship—reading with a former housemate in Austin; visiting a book club of twenty-five women hosted by my former babysitter, who had an enormous birthday cake waiting for me; reading at a pub in Rochester with college friends I hadn’t seen in thirty-five years; and a stop at a Binghamton diner, for a big breakfast with some old friends, that unexpectedly turned into a celebration when they brought their families and friends with them, took over an entire section of the diner, and made me go out to my car to bring in a box of books for them to buy—a joyous celebration if there ever was one.

And then there was the New York event, at my hometown library, the very library I used to walk to by myself during the lonely years after my sister died. My childhood sanctuary.

When I walked in and saw my family, my old neighbors and high-school friends, even my high-school English teacher, all smiling and ready to buy a stack of books, I had to fight off tears. They had come to celebrate me, but they didn’t realize that so many of them had played a role in making me who I was, and thus had helped to create my story along with me. I told myself to embrace it. Not to be modest and say, “Oh, it’s nothing, it’s just a little book.” I allowed myself to enjoy this celebration of my—our— accomplishment.

When I walked in and saw my family, my old neighbors and high-school friends, even my high-school English teacher, all smiling and ready to buy a stack of books, I had to fight off tears. They had come to celebrate me, but they didn’t realize that so many of them had played a role in making me who I was, and thus had helped to create my story along with me. I told myself to embrace it. Not to be modest and say, “Oh, it’s nothing, it’s just a little book.” I allowed myself to enjoy this celebration of my—our— accomplishment.

Now, looking back, I see that I had to learn not only how to celebrate myself in the most common or superficial way—to toast, to cheer, to publicly revel in an accomplishment, to literally or metaphorically frame it and hang it on the wall—but also in a deeper, more Whitmanesque way: by honoring my craft, my art, my spirit, my SELF, and by adding to this personal celebration a species of generosity and gratitude—which, by the way, pervades Whitman’s seemingly egocentric poem as well.

And now, I understand that I need to share the story of my story with others, to encourage other writers, including those students in my program at Wilkes, to find their own ways to celebrate their work, as I did, and not to succumb to all those negative messages they receive from the rest of the world to mind their manners, keep it to themselves, what makes you think anyone would care? And instead to be proud of their hard work and their talent, and to celebrate it. With pride. With gratitude. With generosity.

So yeah, it took me a few decades, but now?

I celebrate myself, and sing myself,

And what I assume you shall assume,

For every atom belonging to me as good belongs to you.

![]()

Leave A Comment