Perfect Timing

(A guest blog written for my friend Lauree Ostrofsky at Simply Leap.)

I’ve been an English professor for 30 years, and let me tell you, it’s a great way to make a living. I love my students, I make my own schedule, and my colleagues are also my dear friends.

But about ten years ago, I started to feel an itch:

I really wanted to be a writer.

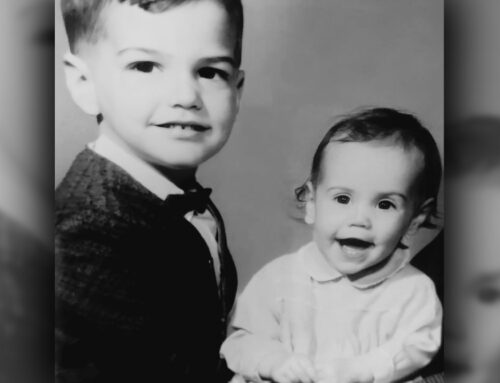

It made sense. As a boy, I loved to read, and in my twenties I fantasized about being an author. So here I was, at 40, thinking about giving it a shot. I resolved to continue to devote myself to my job, but also to write stories whenever I could, in my spare time.

But I soon found that “spare time” was hard to come by. I know that the popular perception of a professor’s life is that it is quite leisurely (smoking pipes, reading books, and imparting wisdom to earnest young people who want to change the world), but my reality was slightly different: my mornings were spent frantically preparing for classes, evenings and weekends were spent reading and grading, and summers spent working (waiting tables, teaching summer classes, and editing). I simply didn’t have much time to spare.

I soon realized I didn’t have much talent, either. I was no John Keats, able to sit under a tree and compose beauty in a single afternoon. I had to plug away for months, revising my stories at least forty or fifty times before they were finished.

In short, I realized that writing was not, and never would be, a hobby for me. It was a job, and I had to dedicate myself to it accordingly. But how? I wasn’t about to quit teaching. I liked it too much, I was making a decent salary, I had health insurance, and my kids would get free tuition. Besides, wouldn’t I miss the comfort and routine a regular job provided?

I kept writing, mostly during long weekends and summer breaks. But I knew I needed more.

Then, ten years ago, two things happened.

First, two of my stories were accepted for publication. Those two phone calls, from Stephanie G’Schwind of the Colorado Review and Linda Swanson-Davies of Glimmer Train, felt like validation: I wasn’t just imagining I could write a good story; two respected editors thought so too.

Second, I was accepted into an artist’s residency—a place called Jentel, near Sheridan, Wyoming. For the month of February I lived in a beautiful house with other artists and had my own writing studio (a tiny log cabin near the main house), where I wrote every day.

Every day. All day.

This was my shot. And I took full advantage of it. The other artists behaved like normal people, working hard during the day and relaxing at night. But I was like a parched man who’d been given an unlimited amount of water, and I kept chugging. At dawn I trudged through the snow to my studio, and I stayed there until late at night, breaking only for meals. It was the most creative, generative month of my life.

This, I remember thinking, is what I want to do. For a living. Every day.

The following August, I had a disastrous re-entry into my teaching life. I was offering classes I had never taught before (big mistake), I took over as department chair (bad timing), and I joined the busiest committee on campus (just plain stupid).

And I stopped writing.

I told myself it was just for the time being. The residency had been a retreat from real life; I could never actually live like that, right? I re-immersed myself into my job.

And quickly grew frustrated. Cranky. Irritable. I had experienced, however briefly, the euphoria of being a full-time writer, and now it all felt so far away. I needed to adjust my teaching routine so it wasn’t so frenetic and reimagine what my writing routine could look like—not just during school breaks and summer vacation, but every day. Even in the very midst of my busiest semester.

Enter friend and life coach Lauree Ostrofsky.

Lauree helped me to figure it out. I put up sticky notes around my office, reminding myself to write. I enlisted the support of my wife, my colleagues, and my friends. I connected with other writers. I bartered with my web-designer friend Paul Carr: free writing instruction and editing in exchange for this website. I rented out office space a block from my home to use as a writing studio. I asked other writers to meet me regularly during the week to write. And I applied to (and was accepted at) another residency.

From the very first week, I saw results. Having to meet other writers at coffee shops meant being accountable: I couldn’t just ignore my designated writing time and catch up on schoolwork. I wrote more often, and for longer periods, until gradually I felt my primary identity evolve—from professor to writer. This wasn’t so much about time allocation (although that was important) as it was about mental focus. After waking up for years thinking of what I was going to teach or what I had to do for an upcoming meeting, I now woke up thinking, “When am I writing today? With whom? And what story will I work on?” Then I would head off to teach my classes, excited about my writing time that afternoon.

I had changed from a professor who occasionally wrote to a writer who occasionally professed.

Now—my son a college graduate, my daughter a junior—I find myself looking forward to the day when I can ditch this profession I love and embrace the vocation I love even more. To the day I can be a writer, full-time. All day, every day. Until then, I will continue to cultivate this new attitude, this new routine, these new priorities.

Or rather, these old priorities. For in a way, I’ve come back around to that little boy who loved to read, that young man who dreamt of being an author. It took me a while—I’m 53 now—but it doesn’t feel too late.

In fact, it feels like perfect timing.