Fiction as Truth

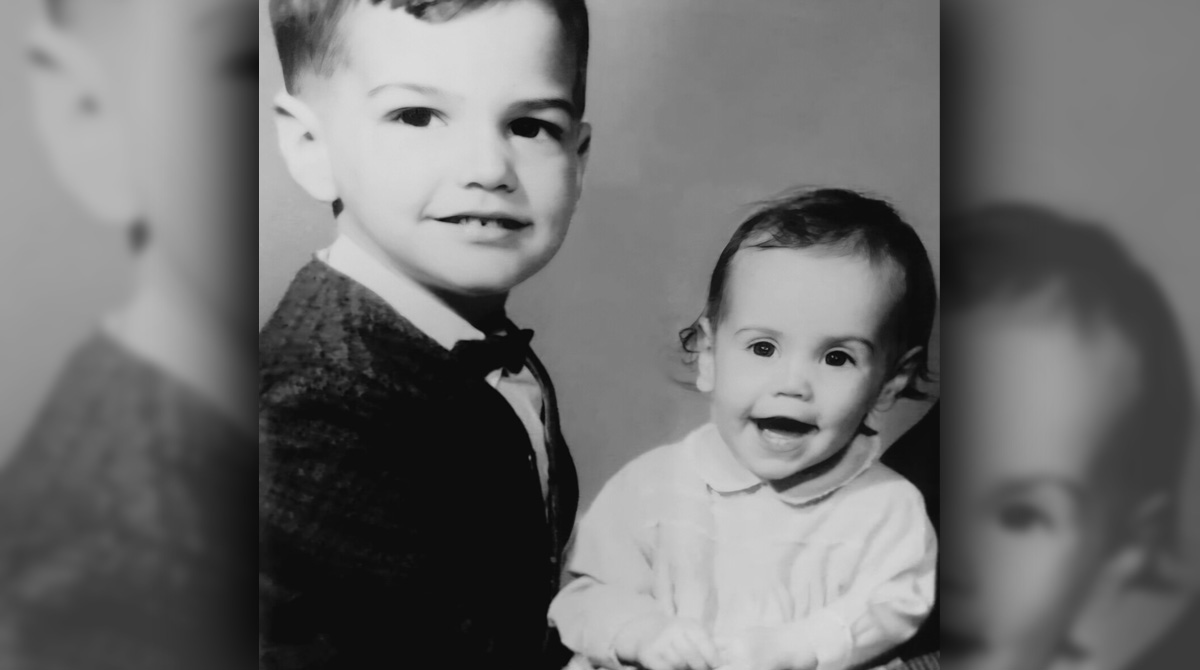

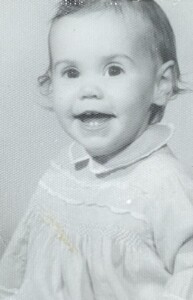

I’m writing this on the publication date of my children’s book, THE MAGIC TICKET (Fulcrum Books), so naturally, I’m thinking a lot about the subject of the story, my late sister Sandra. (The book is about a boy whose sister dies, after which he seeks solace in books and finds a sanctuary in his local library. The “magic ticket” of the title is his library card.) Sandra was two years my junior, and based on what I’ve been told, along with my speculation, instincts, untrustworthy memory, understanding of myself, and knowledge of how protective and loving I was toward my second sister Marisa, who was born six years after Sandra’s death, I’m guessing that Sandra and I must have been very close. So it stands to reason that I must have been devastated when she died, suddenly, in the middle of the night, a few weeks before her second birthday, during that “bridge” period between babyhood and childhood, while I lay sleeping in the room next to hers, sick with a stomach virus.

But I don’t really know.

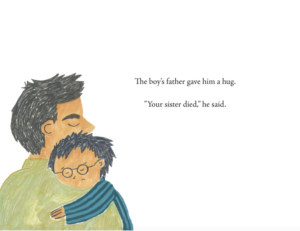

In the book, the boy wakes up to find his sister’s crib empty and when he goes downstairs he is hugged by his father, who tells him, “Your sister died”—a line that came not from my memory or reality but from a suggestion by my writing friend Deann who intuited (correctly, as it turns out, since that kind of truth-telling has been singled out by child psychologists as much better for children than vague and confusing euphemisms like “she’s gone” or “she’s in heaven now”) that for a children’s book, I needed to plug in a direct statement about what happened, instead of depicting the boy as “confused” and “lost” as I did in the book’s first draft—and in reality, I don’t remember what my father or mother said to me, if they were able to say anything at all.

In the book, the boy wakes up to find his sister’s crib empty and when he goes downstairs he is hugged by his father, who tells him, “Your sister died”—a line that came not from my memory or reality but from a suggestion by my writing friend Deann who intuited (correctly, as it turns out, since that kind of truth-telling has been singled out by child psychologists as much better for children than vague and confusing euphemisms like “she’s gone” or “she’s in heaven now”) that for a children’s book, I needed to plug in a direct statement about what happened, instead of depicting the boy as “confused” and “lost” as I did in the book’s first draft—and in reality, I don’t remember what my father or mother said to me, if they were able to say anything at all.

I think I remember the police running up the stairs.

I think I remember my babysitter showing up to the house, my parents gone (to the hospital) at that point.

I think I remember my brother and I being taken to our next-door neighbors’ house.

I think I remember the priest coming to our house days later and announcing, “You have an angel in the family!”

But maybe I was just told all those things, and they were locked in as memories. Years later, after hearing that I thought Sandra had caught my illness (I was very sick that night ) and died from it, and that I had always felt guilty about it, my mother reassured me that Sandra had died not of my illness but of a staph infection. Years later, my brother, also out of love, told me what he remembered from that terrible night. So I don’t know if what I am picturing in my mind is something I actually remember or if they are merely images that flared up and locked into my brain whenever something was described to me, so desperate was I to have some memories, any memories of that night, or of my sister, or of where I was when it happened, which nobody has ever been able to remember. My parents were understandably wrecked for months afterwards, leaving me to assume that the best thing I could do was to be quiet, to read my book (I loved The Wonderful World of Peanuts paperbacks, available for 40 cents in grocery stores back then), and not to bother my grieving parents.

But maybe I was just told all those things, and they were locked in as memories. Years later, after hearing that I thought Sandra had caught my illness (I was very sick that night ) and died from it, and that I had always felt guilty about it, my mother reassured me that Sandra had died not of my illness but of a staph infection. Years later, my brother, also out of love, told me what he remembered from that terrible night. So I don’t know if what I am picturing in my mind is something I actually remember or if they are merely images that flared up and locked into my brain whenever something was described to me, so desperate was I to have some memories, any memories of that night, or of my sister, or of where I was when it happened, which nobody has ever been able to remember. My parents were understandably wrecked for months afterwards, leaving me to assume that the best thing I could do was to be quiet, to read my book (I loved The Wonderful World of Peanuts paperbacks, available for 40 cents in grocery stores back then), and not to bother my grieving parents.

But that kind of confusion and isolation wouldn’t make for a very good children’s story, right? So I went with the clearer, more compassionate version, as in the page I’m reprinting here. And I think it worked out well.

All of this is to say that I’ve found it enormously helpful to fictionalize my life story—a form of narrative therapy, I suppose. It’s so much more effective, oddly enough, than a diary or memoir or even talk therapy, because to fictionalize your story, to tell it in third person, allows you to look at yourself as the main character in the story of your life, acting instead of reacting, and that in turn allows you to empathize with yourself – Look at this poor kid, his sister died and he’s alone in his room, reading his book to the empty crib. It frees you from the usual self-blame or depression (My sister died, and I felt responsible for her death, so I felt guilty for years,) and allows you to “resolve,” through “fiction,” something that’s seemingly irresolvable—but just as true. In other words, the story that I was a boy who was hit by a tragedy but then found solace, even happiness, through books, is just as true, if not more so, than the story that I was a sad boy who was so devastated by his sister’s death that he became a self-conscious introvert from that day forward. It’s not fiction-as-lying or fiction-as-daydreaming; it’s fiction-as-truth. It’s structuring and crafting and staying focused on the real story rather than getting caught up in self-pity. (Not that there’s anything wrong with self-pity—it’s so much better than denying your right to your feelings in that “get over yourself” way.) Fictionalizing your self, and your life, tells the truth from a different perspective–the unconscious, capital-T truth, which is truer than the conscious truth.

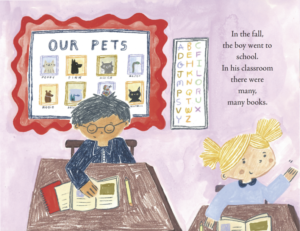

Another example of this came unexpectedly from the book’s illustrator, Kateri Kramer, in the choice she made when she illustrated the page that follows the death of the boy’s sister, when the boy goes to school the following fall. This is where Kateri Kramer, chose to put a hint of a smile on the boy’s face as he reads from a book.

Another example of this came unexpectedly from the book’s illustrator, Kateri Kramer, in the choice she made when she illustrated the page that follows the death of the boy’s sister, when the boy goes to school the following fall. This is where Kateri Kramer, chose to put a hint of a smile on the boy’s face as he reads from a book.

There’s no way I would have done that if I had illustrated the book. I would have depicted the boy as overwhelmingly sad, sitting in the corner, reading quietly. That’s how I remember myself. (And there was nothing in the text—“In the fall, the boy went to school. In his classroom there were many, many books”—to suggest the presence of that shy little smile to Kateri.) But here again, “fiction” is truer than fact. Truth be told, I was happy when reading, even soon after my sister’s death—and it was an intensely personal, secret happiness. And that’s what that hint of a smile conveys—an inward, barely detectable joy in the act of reading. How did Kateri know to depict me as I really was, rather than how I remember I was?

I asked her that question, and in response, she told me that by drawing that tiny smile, she was trying to indicate “the shift from sad/confused to hopeful” that occurs over the course of the book: following his sister’s death, the boy starts reading to her, just as he had done when she was alive, and in so doing, he re-connects with her. In other words, Kateri illustrated that page with the big picture of the story in mind without any input from me. And again, in crafting fiction, she hit on the Truth more accurately than if I had told her the truth according to my memory.

What has evolved, then, since the writing of this book, even more so since its publication and some public readings of it now that I’m on this book tour, is that I’ve been feeling a blossoming tenderness toward my childhood self, and a more joyous connection with my sister Sandra. Or rather, a more easeful relationship with her. I’m as surprised by this as much as anything else. I mean, it’s been almost six decades since she died. In fact, while I thought the book would be difficult to read in public, the only page that makes me choke up a bit is not the one in which the father says, “Your sister died” (after all, that page is made up)—but the one in which the boy resolves, Someday, I will write a story about my sister. That’s when the tears spring to my eyes. Why does that last page move me so? I think it’s because it surprised me so much when I wrote it. It was, for me, a rather startling private (and now public) admission that at that young age, I wanted to be a writer.

And here’s the point: it’s not true that I thought to myself that someday I would be a writer. I would never have had such a thought at that age. or even ten years later. But it sure as hell is True. It took me decades to realize that little boy’s fictional/truthful confession, even to state that intention out loud, to say nothing about acting on it.

But now, well, look at you, David—you’re a writer.

And what do you know, you’ve written a story about your sister!

Once upon a time, there was a boy who was very happy. Then, one day, his sister died, and he was sad for the rest of his life.

Once upon a time there was a boy whose sister died. Then, one day, he discovered the magic of books, and he read to his sister every day, finding joy and comfort in the power of story.

Truly Moving Dr.Hicks

This is wonderful. Thank you David