Half Breed

That’s what my father used to call me. He was American (his ancestors were English, Irish, and Dutch), and my mother is Italian. At 17, she was lured from her beautiful homeland by the handsome Navy sailor who, while stationed in Naples during the Korean War, played for the Pozzuoli team on the court located right behind her apartment building. Love at first sight. Literally. Because it certainly wasn’t love at first sound—he didn’t know Italian, and she didn’t know English—or love at first touch, since her parents required an escort for every date.

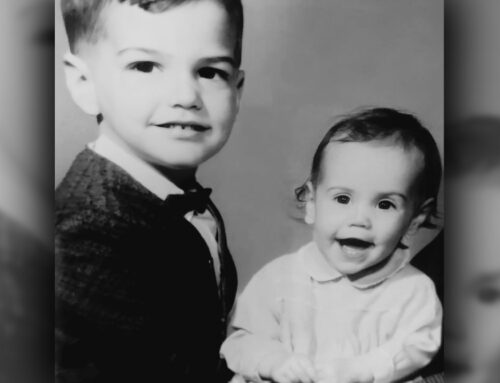

After making the ten-day journey by ship, my mother immediately did her utmost to assimilate into American culture: she learned English by studying, taking night classes, and watching a lot of television. Nobody in her new world spoke Italian, so it was up to her to learn English if she wanted to communicate. And once my brother and I were born, she was so determined to assimilate that she refrained from speaking to us in Italian.

So even though I was sometimes called “Dav” at home (short for Davide, or Davidino), I did not, unfortunately, grow up bilingual. But I did grow up as the beneficiary of my father’s promise to my nonno and nonna, that he would bring their daughter back for a visit every two years, no matter what. So every two years, I went to Italy.

The American side of my family is rich with good, hard-working, kindhearted people, who are not especially adept at showing affection. This goes way back. My father loved to tell me that there was a guy named Hicks on the Mayflower.

“In other words,” I said, “you descended from losers and criminals who couldn’t make it in England.”

“We,” he told me. “We descended from losers and criminals.”

He once showed me a photo album of Hicks men, going back a few generations. One held a shotgun in one hand and a dead rabbit in the other. Another stood with his arms folded, scowling at the camera. Another didn’t seem to have any lips. They were hard people from hard places cut off from their hard land during hard times that had hard names like the Famine and the Great Depression. Little wonder they had trouble expressing their feelings.

My Italian relatives, on the other hand, lived in the midst of their history and hardships, in their sunny, sea-swept land, and had absolutely no trouble expressing their feelings. And when I was a kid, I wanted nothing more than to do that. Whenever I went there, I was free to kiss and be kissed, cry and laugh, eat as much as I could possibly eat, and then eat some more. I was loved, openly and unabashedly. I was understood. It felt as if I had left home to find home.

I was a half-breed, yes, but embracing one half seemed to necessitate an unkind rebuke of the other half.

As I got older, I saw that I was guilty of romanticizing my Italian side, and unfairly indicting my American side. I saw that my Italian family, demonstrative and passionate and affectionate, nonetheless had problems just like any other family. And my American family, comparatively reserved, even muted, was actually quite loving in their own way, and predictable in a way that I used to find boring but gradually saw as reliable and comforting.

Born a Gemini, I had been fated to live a split life, never feeling like I had a true home. But as Geminis age, their twin stars come together to form a single personality. And that’s what has happened to me. I’m half-Italian. I’m half-English/Irish/Dutch. I’m a full-blooded Italian-American.

A half-breed. And proud of it.