“A Beautiful Collaboration”: Writing and Illustrating a Children’s Book Together

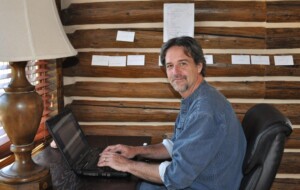

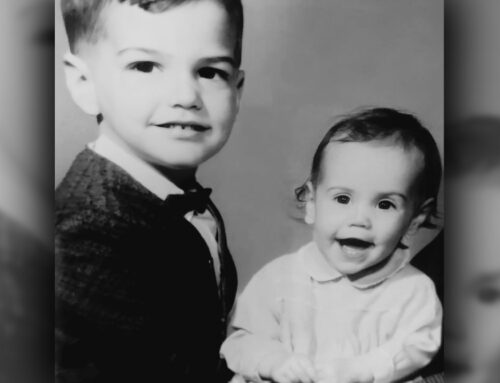

In most cases, a children’s book is written by the author, the author is fortunate enough to find a publisher, and then the publisher assigns an illustrator to the project. But in the case of THE MAGIC TICKET , the author, David Hicks, first wrote a deeply personal, autobiographical story, then approached his talented friend Kateri Kramer to see if she was interested in illustrating it. The two then collaborated on the book, shaping and revising it together based on their shared ideas, and then approached the publisher together with the finished product. And it worked! Fulcrum Books is publishing it in July of this year.

Here the author and illustrator talk about their unusually collaborative process:

(Kateri:) You’ve primarily written adult fiction and taught adult creative writing classes. What was the catalyst for The Magic Ticket and how was the process for writing a picture book different?

(Kateri:) You’ve primarily written adult fiction and taught adult creative writing classes. What was the catalyst for The Magic Ticket and how was the process for writing a picture book different?

(David:) Same kind of catalyst, very different process. :-) My stories and novels, while fiction, are all based on something that happened to me, an event or encounter that changed me in some way, small or big. That’s no different for this children’s book, which is based on the biggest thing that happened to me, which is that when I was a boy, my sister died suddenly, in the middle of the night, and my family, along with my view of myself, my very being, was forever changed. But the difference in this event, and thus in the process of writing it, is that it was too big for me to get a handle on it. That’s why I’d been avoiding it. In order to write it, therefore, I had to make it really simple. So I reverted to a formula, a lesson I teach my students about story structure: Once upon a time . . . . Then, one day . . . .

(David:) Same kind of catalyst, very different process. :-) My stories and novels, while fiction, are all based on something that happened to me, an event or encounter that changed me in some way, small or big. That’s no different for this children’s book, which is based on the biggest thing that happened to me, which is that when I was a boy, my sister died suddenly, in the middle of the night, and my family, along with my view of myself, my very being, was forever changed. But the difference in this event, and thus in the process of writing it, is that it was too big for me to get a handle on it. That’s why I’d been avoiding it. In order to write it, therefore, I had to make it really simple. So I reverted to a formula, a lesson I teach my students about story structure: Once upon a time . . . . Then, one day . . . .

So I decided to use this structure to write about the most formative event of my childhood, as a starting point: Once upon a time there was a boy who lived in a very happy household with a loving mom, a kindhearted dad, a big brother he admired, and a little sister he adored. Then, one dark night, his sister died. And there it was, my story, in its simplest form. I then set about filling it out–it could be a memoir or novel–I figured. Then again, I thought, I could keep it simple, and it might have more power that way. So I tried it as a children’s story, even though I didn’t know the first thing about writing a children’s story.

“Then again, I thought, I could keep it simple, and it might have more power that way.”

How about you? You’re a writer and a creator, but how did you become an illustrator? How is illustrating a children’s book different from the kind of drawing/illustrating you’ve done in the past?

I’ve been doing visual art since I was very little because my dad was a painter. He used to give me and a few friends drawing lessons on Saturdays so I think being an illustrator felt really natural. It wasn’t until 2020 when I took a class with The Goodship Illustration when I realized that being an illustrator was something I could do as a job (or a side-job). In the past I’ve done a lot of brand identity illustration (everything from logos, to brand iconography and assets for websites), but a children’s book is a very different ballgame. While both types of illustration have to have a cohesive feel and belong together, the consistency required in a picture book is at a different level. This was the first time I had to make sure that the proportions of the characters, the decorations in the rooms, and the coloring of different objects like the wagon or the cat were the same on page one as they are on page 30. There’s a lot of organization and checking then rechecking, then rechecking again that goes into picture book illustration.

I’ve been doing visual art since I was very little because my dad was a painter. He used to give me and a few friends drawing lessons on Saturdays so I think being an illustrator felt really natural. It wasn’t until 2020 when I took a class with The Goodship Illustration when I realized that being an illustrator was something I could do as a job (or a side-job). In the past I’ve done a lot of brand identity illustration (everything from logos, to brand iconography and assets for websites), but a children’s book is a very different ballgame. While both types of illustration have to have a cohesive feel and belong together, the consistency required in a picture book is at a different level. This was the first time I had to make sure that the proportions of the characters, the decorations in the rooms, and the coloring of different objects like the wagon or the cat were the same on page one as they are on page 30. There’s a lot of organization and checking then rechecking, then rechecking again that goes into picture book illustration.

“I’ve done a lot of brand identity illustration . . . but a children’s book is a very different ballgame.”

Speaking of process, how did you go about writing The Magic Ticket and what was your revision system like? Was it harder than a full-length adult book because there were such strict boundaries around word count?

My first draft was, I think, around 900 words, but it wasn’t too difficult to pare it down to the 700-word expectation for picture books–in fact, I rather enjoyed the process, whereas in novel-writing, deleting words and scenes is arduous and painful. The big difference was in my focus on diction and sound, as opposed to scene or character development–it felt more like poetry than narrative. When I revised my current novel (from a whopping 170,000 words to a closer-to-normal 98,000), I hacked away at scenes and secondary characters, based on what was and what was not essential to the story. But with The Magic Ticket, the story was already at its essential level, already bare-bones, so I acted more like a poet, focusing on sound and rhythm on a word-by-word basis. Even now, as you and I are making final revisions to the galleys, I’m deleting words based on sound and rhythm–and on something I’ve never had to consider before: the look of the page. Once I saw the galleys with your beautiful illustrations, I could also see that some pages were too crowded with my text, and that some of your illustrations rendered some of my text unnecessary. For example, do we need the words, “His mother was very, very sad” if your illustration (of the boy’s mother lying on the couch, despondent) conveys that sadness? These are the kinds of revisions I really enjoy, not only because they are brand-new to me, but also because of the collaborative aspect . Writing is typically a very lonely occupation, so it’s been great fun to co-author this book with someone who is so creative in a way that I’m decidedly not. (I mean, even my stick figures are embarrassing.)

My first draft was, I think, around 900 words, but it wasn’t too difficult to pare it down to the 700-word expectation for picture books–in fact, I rather enjoyed the process, whereas in novel-writing, deleting words and scenes is arduous and painful. The big difference was in my focus on diction and sound, as opposed to scene or character development–it felt more like poetry than narrative. When I revised my current novel (from a whopping 170,000 words to a closer-to-normal 98,000), I hacked away at scenes and secondary characters, based on what was and what was not essential to the story. But with The Magic Ticket, the story was already at its essential level, already bare-bones, so I acted more like a poet, focusing on sound and rhythm on a word-by-word basis. Even now, as you and I are making final revisions to the galleys, I’m deleting words based on sound and rhythm–and on something I’ve never had to consider before: the look of the page. Once I saw the galleys with your beautiful illustrations, I could also see that some pages were too crowded with my text, and that some of your illustrations rendered some of my text unnecessary. For example, do we need the words, “His mother was very, very sad” if your illustration (of the boy’s mother lying on the couch, despondent) conveys that sadness? These are the kinds of revisions I really enjoy, not only because they are brand-new to me, but also because of the collaborative aspect . Writing is typically a very lonely occupation, so it’s been great fun to co-author this book with someone who is so creative in a way that I’m decidedly not. (I mean, even my stick figures are embarrassing.)

“[Revising a children’s book] felt more like poetry than narrative.”

How about you? What’s it like to bring to life someone else’s words, someone else’s story, while also “making it your own” and adding your own ideas/images? And what’s it like to put your heart into an illustration only to have the author request a modification of that illustration?

It was a lot more challenging than I thought it would be (probably part of the reason I procrastinated…overthinking it!). I will say that my experience might have been a-typical because I didn’t have traditional art direction (could have made it easier or more challenging) and you and I have known each other for a while. If I didn’t know the author I might not have been so worried that they wouldn’t like it. However, I think the fact that we do know each other, and have worked together, made me really think and rethink and rethink again, which was good. In the future, I know that I will need to take more time for sketches and exploration, which anxiety/full-time-job/artist-block/first-time-illustrator jitters didn’t afford me this time around.

It was a lot more challenging than I thought it would be (probably part of the reason I procrastinated…overthinking it!). I will say that my experience might have been a-typical because I didn’t have traditional art direction (could have made it easier or more challenging) and you and I have known each other for a while. If I didn’t know the author I might not have been so worried that they wouldn’t like it. However, I think the fact that we do know each other, and have worked together, made me really think and rethink and rethink again, which was good. In the future, I know that I will need to take more time for sketches and exploration, which anxiety/full-time-job/artist-block/first-time-illustrator jitters didn’t afford me this time around.

Because I didn’t have that traditional art direction, I relied on you very heavily for input about how illustrations looked, consistency, variation in perspective, and color. I’m immensely grateful that you were so thoughtful and attentive to it. Not to mention this is YOUR story and I very much wanted to represent it in a way that felt accurate.

We kept revising both the text and the illustrations through to the end of the process. Are you happy with the way the text turned out? How does marketing a children’s book differ from an adult book?

Yes, I’m delighted with how it turned out! I’m always happy when an editor forces me to cut a certain number of words; it compels me to adopt an economy of language that’s always good for writing (in any genre). In this case, because of how the layout changed the book’s pagination, we realized we needed to trim a couple of pages from the end of the book, which forced us to trim both words and images from the final four pages, and I think it made the book better. I certainly loved how your new illustrations for those final pages turned out. So of course that (the limited number of pages and words required of a picture book) is nothing I would even have to think about with a literary novel; but I enjoyed the challenge it presented us with.

Yes, I’m delighted with how it turned out! I’m always happy when an editor forces me to cut a certain number of words; it compels me to adopt an economy of language that’s always good for writing (in any genre). In this case, because of how the layout changed the book’s pagination, we realized we needed to trim a couple of pages from the end of the book, which forced us to trim both words and images from the final four pages, and I think it made the book better. I certainly loved how your new illustrations for those final pages turned out. So of course that (the limited number of pages and words required of a picture book) is nothing I would even have to think about with a literary novel; but I enjoyed the challenge it presented us with.

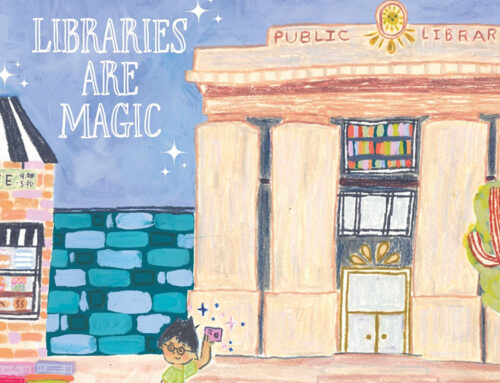

As for marketing, you would know better than I, but for me it’s been markedly different. I’m not only presenting myself in a different way (that is, as a children’s author, a warmer/friendlier version of my serious-novelist persona); but I’m working with a different audience. With my novels, I pitched readings at bookstores. Simple. With The Magic Ticket, I’m talking with schools, libraries, grief-counseling centers (because of the Magic Ticket’s subject matter), and yes, bookstores too–but for obvious reasons giving a storytime reading to children is very different from a literary reading to adults. I’m marketing myself more than the book, in a way, and when I pitch the book, I’m pretty much giving the whole story away (it’s only 700 words, after all), opposed to just a glimpse of it (for a 100,000-word novel). At the same time, just as with my last book tour for my novel, it’s all about connections. It’s all about believing in the book.

“[I]t’s all about connections. It’s all about believing in the book.”

For you, what’s it been like to wear two different hats, one business-y (marketing) and one creative (illustrator). And what are your hopes for this book?

It’s both a challenge and a super cool opportunity. I think it gives me the opportunity to think about marketing needs differently because if we want something special for the book like a promo sticker, I can just illustrate it. On the other hand, it’s challenging because I’m not just living in the realm of the illustrator, I’m also balancing all the marketing needs. My biggest hope for this book is that it opens up conversations about loss and grief for both children and parents/counselors/librarians/guardians. Children today are facing so much more grief, whether it’s loss of a family member, or dealing with the consequences of Covid, or dealing with the fear/grief/uncertainty of our world (whether from hearing it themselves, or feeling the uncertainty from guardians). I think that talking about all of that at an early age means that children will feel more able to continue those conversations, and feel their feelings as adults. Or at least that’s my hope.

It’s both a challenge and a super cool opportunity. I think it gives me the opportunity to think about marketing needs differently because if we want something special for the book like a promo sticker, I can just illustrate it. On the other hand, it’s challenging because I’m not just living in the realm of the illustrator, I’m also balancing all the marketing needs. My biggest hope for this book is that it opens up conversations about loss and grief for both children and parents/counselors/librarians/guardians. Children today are facing so much more grief, whether it’s loss of a family member, or dealing with the consequences of Covid, or dealing with the fear/grief/uncertainty of our world (whether from hearing it themselves, or feeling the uncertainty from guardians). I think that talking about all of that at an early age means that children will feel more able to continue those conversations, and feel their feelings as adults. Or at least that’s my hope.

“My biggest hope for this book is that it opens up conversations about loss and grief for both children and parents . . .”