Diamond Dash

During the long wait in line with thousands of children and their parents and guardians–a line that wrapped all the way around Shea Stadium and then some–I had twice resolved to leave, had twice determined that whatever the Diamond Dash was it just couldn’t be worth it, standing for over an hour in the Flushing heat; furthermore, I knew that in order to establish a trusting co-parenting relationship with my now-officially- ex wife, I needed to bring our son back on time after such special outings.

During the long wait in line with thousands of children and their parents and guardians–a line that wrapped all the way around Shea Stadium and then some–I had twice resolved to leave, had twice determined that whatever the Diamond Dash was it just couldn’t be worth it, standing for over an hour in the Flushing heat; furthermore, I knew that in order to establish a trusting co-parenting relationship with my now-officially- ex wife, I needed to bring our son back on time after such special outings.

But Stephen, who was eight and insistent, had decided it was worth it, whatever it was, so we persisted, shuffling our feet forward every few seconds, Stephen standing behind me, holding on to the sides of my t-shirt, burying his face into the small of my back, and wiping his forehead on me as he matched his steps with mine. He came around and held my hand as we neared the center- field gate. Then, when we finally walked through the gate onto the playing field and heard the stadium usher say, Stay on the warning track please this way, he pulled his hand from mine.

I had left my marriage three years earlier, when Stephen was five. It was late at night in early January, two weeks after that miserable Christmas when Stephen and I shared the same stomach virus and took turns vomiting all night. I had put him to bed, rubbed his back until his breathing slipped into sleep, and then spent an hour in the basement, sitting on the concrete floor with my head in my hands. Finally I went upstairs, told my wife I no longer loved her, then dodged the coffee table she heaved at me. She threatened to wake Stephen if I didn’t get out of her house immediately, so I spent the night at my sister’s.

The next day, after being told I’d better be the one to explain all this to him, I picked up Stephen and drove him to the pizzeria in town. Stephen bent his head down as I ordered us a couple of slices, then kept it down as I guided him over to a booth. As I sat down I noticed some kid, who looked to be Stephen’s age, firing at men who popped up out of nowhere in a video arcade game. In a split second the kid had to decide if the figure was a hero or a villain, then shoot or hold fire. Our pizza slices sat on paper plates before us.

“I’m not leaving you,” I told Stephen. “I’m leaving Mom. Your mother.” I tried hard not to promise him I would come back home and make it right. I sought out his eyes, hidden under his baseball cap. But when he looked up at me, I looked back over at the kid at the video game.

“You are–you’re leaving me,”he said, and his head lowered and jerked, his face dissolving before my eyes. Harsh breaths grated and caught in his throat. I reached out to keep his forehead from touching the pizza sauce. “I woke up and you were gone,” Stephen said through his chokes. “Mom said you just left.”

I considered telling him how important it was to love the person he married when he grew up, to make sure. I considered explaining how it had all happened, how his mother and I had been too young to marry, how we hadn’t yet learned to love ourselves, how we had fought all the time before he was born. I considered apologizing to him for ruining his life. I thought about the articles I had just read, the ones about children of divorced households, how they were more likely to become addicted to drugs, commit violent crimes, and grow into coldhearted atheists who hated their fathers. Stephen abruptly lifted his head.

“Hey, why don’t you just come back?”

He thought the solution so simple that, for a moment, his eyes brimmed with certainty. Then they again collapsed, and his tears dropped down onto the oil of his pizza, his shoul- ders convulsing. Just like me, he could cry without making a sound. Nothing will ever be as hard as this, I wanted to tell him, but I knew that that too would be a lie. Instead I just watched as he slipped away from me across the table, the space between us opening up like a canyon, and I understood that nothing for him would be easy for a long time, and nothing I could say would help him. All the months I had considered leaving, all the debating and bargaining–I had known it would destroy him, and that had kept me from acting on it. But I had never put a face to the destruction. Here it was, in front of me, and I had at the ready no offerings of solace or hope.

As we stepped through the center-field gate and entered the ballpark, I saw immediately what the Diamond Dash was. The line of kids and adults turned left and followed the warning track to the right-field corner, then turned right and headed toward home. Upon reaching first base, the kids made a sharp right and took off, dashing from first to second, from second to third, and then from third to home, while the grownups continued to stroll down the first-base line, watching and shouting encouragement, until they met their little ones at home plate and ushered them out of the ballpark. A dash around the diamond. Stephen quickened his pace, and I lengthened my gait to keep up with him.

One Saturday in June two years earlier, when Stephen was six, we sat together on the baseball field at the Brewster town park, near the reservoir. Across the water, on Route 22, a truck rumbled by, cutting over from one highway to another, heading down toward the Bronx. Maggie and I were legally separated, communicating mostly through lawyers.

“Are those the same swans we saw last time?”Stephen asked, pointing.

I looked up, nodded, and then noticed, on the far side of the reservoir, a car that looked like Maggie’s rolling slowly on the shoulder, stopping under a tree. Fire-engine red.

“They’re beautiful,”I said. “Though territorial.”Stephen threw the baseball up in the air and caught it in his new glove, waiting for me to define territorial. Then his fist clenched around the ball. “They decide a pond is theirs,”I explained, “even if it really isn’t, and they dominate it. They kill ducklings late at night.”

“Why don’t the ducks just stick together and fight back?”Stephen asked.

I watched the swans swim in unison, dipping their long necks toward each other–such enmity, such grace . “I guess they’re afraid,”I said.

“Do you still not love Mom?”Stephen asked.

“I’m sorry,” I said. “I don’t.”

“You love someone else now?”He looked away as he asked this.

“I did,”I said . “But she left.” I tore up a tuft of grass, fisted it in my hand. I was sitting on the infield. Stephen was standing a few feet away from me, on the dusty base path between first and second, between the infield and the outfield, shifting his weight from one foot to the other, pounding the baseball glove with his little fist.

He nodded. “Mom still loves you,” he said, “even though you left .” He kicked the bat with his foot. “So now you must love her again if you don’t love anyone else. You have to love someone.”

I stared at the torn grass in my hand. “I love you,” I said. Stephen shook off his glove and picked up his new bat. He tried to toss the ball up in the air and hit it, but he swung and missed each time. After the fourth miss, he flung the bat as far as he could. It thudded and bounced awkwardly on the dirt near second base. “I hate this bat! It’s too heavy,” he cried, the wrath in his voice, the redness of his face, all new.

I could see that the bat, which I had given him for Christmas, was too heavy, and that his arms were in discord with the rest of his body, but that soon, in a few years perhaps, he would be strong enough to rip line drives with a smooth, level stroke. But who would teach him how to swing, how to shift his weight from back leg to front, how to follow the ball with his eyes right into the catcher’s mitt?

Stephen crumpled his body to the ground and began flinging pebbles and clumps of dirt.

“I was lying on the floor in the family room every night,” I told him, “after I read to you and rubbed your back, after you fell asleep. After your mom fell asleep .” I began to curl my face into my armpit, in imitation of how I looked on the floor, but the feeling was too close, right in my breath. I looked back over to the swans.

“If you come back, I’ll be good all the time and you won’t be sad, ” Stephen said. “And if you do get sad you can just come in bed with me like you used to and I’ll rub your back now.”

I shook my head, still staring down.

“Mom says you’re going to hell,” Stephen said.

A cyclist rode by, and I looked over to the dirt path she was following into the woods. Stephen and I had ventured down that path many times, but I still didn’t know where it ended up. The last time we had walked there, in the fall, he had found a butterfly on the ground, its wing bent, and thought that by picking it up and holding it, he could save it.

Across the ballpark on the left-field wall of Shea Stadium were the jersey numbers and names of famous Mets: Tom Seaver and Gil Hodges, men I had watched with rapture when I was Stephen’s age, men of strength, confidence, and grace. I considered telling Stephen about Seaver, about his near-perfect game I had witnessed so many years ago, but it would have taken too long to explain. I bent down in midstride to scoop up a bit of clay from the track, and Stephen paused and turned back to me, holding out his hand so I would hurry, so we would not lose our place in line.

“Why did that man call it a warning track? ” Stephen asked as we crunched along the outfield wall and turned toward home, and I heard his question in some arid distance, as if he had asked in his thin voice through a tin can on a string from his room back in Brewster all the way to the other tin can where we were now in Queens.

When he was four, Stephen and I sat on the living room couch one afternoon as I prepared for the class I was teaching that night. Stephen was reading a pop-up ABC book featuring a variety of insects, turning a page whenever I did. Maggie was in the family room, blasting an old Pat Benatar album while she vacuumed the carpet.

Stephen was inventing a narrative to go with the pictures of the insects, occasionally identifying a letter. “B,” he would call out, over the loud music. “Butterfly. Butterflies are pretty. They fly with their pretty wings and drink all the flowers.” Then he would flip the page.

“Shh.” I put my finger to my lips as I flipped the page of my book backward. “Go in your room if you want to read out loud.” The music pounded. The vacuum whined.

“C. Crocodile. Butterflies go to see their friend Mister Crocodile. ” Another turn of another page.

“Please,” I said . “Daddy’s trying to work.” I held the book closer to my face. Love is a battlefield.

“D,” he said next. “Doggie. Daddy Doggie.” He hadn’t even turned the page. “Daddy Doggie is cranky today.” Stephen’s voice rose to be heard over the music. He was shouting now, his breath close to my ear. “He can’t see the pretty colors of–”

I snapped my book shut with one hand and clamped the other over Stephen’s mouth, pressing my palm hard against it for a few vicious seconds, his head forced against the back of the couch. His eyes widened as he struggled to breathe.

When I let go, he drew in a long breath, tears already starting to roll down his cheeks. And when he finally exhaled, he let out a long, loud scream.

I had been on the playing field of Shea Stadium once before, about thirty years ago, when I was around Stephen’s age, when my father took me to Fan Appreciation Day. I don’t remember anything about the first game of the doubleheader. But between games, clutching the wooden end of the poster I had made, I was ushered to a long line of kids, a line that, like the one I was on with Stephen, wrapped around the stadium and led us to the center-field gates, where we divided into two lines and streamed toward first and third. For days I had dreamed of the feel of the grass beneath my feet, of seeing my heroes watching me from the dugout, appreciating my poster. But once on the field, I frantically began to search for my father in the stands near third base . With every step my anxiety increased as I walked the length of the outfield grass toward the infield, holding my poster with both hands, my eyes spanning the stands, darting from the concrete aisles to the blue and orange seats, trying in vain to locate his gray windbreaker. When I reached third base, I dropped the poster and began to run toward the exit behind home plate. When I reached it, there he was, standing a reasonable distance from the rest of the parents, a snuffed-out cigarette at his feet. I clasped my arms around him, breathing in the familiar, dusky smell of his jacket.

A few months after I left my marriage, Stephen and I sat on my bed in my new home, the tiny cabin in Katonah I had rented after spending a month at my sister’s. On the paneled bedroom wall I had taped twenty-three of Stephen’s firstgrade drawings. In one of those drawings, stick figures in red crayon stood side by side on orange construction paper. There was a mommy, with a red smile and a tuft of blonde hair; a daddy, tall, with black hair; and a little boy, the slightest of the three. A strange man stood between the boy and the daddy, a silly, thick grin plastering his face. The tallest member of this crayon portrait, he was clearly not of the family. And although the stranger was laughing, his head was on fire. An orange blaze raged up from inside his skull, the top of which had been blown off.

When Stephen handed the drawing to me, I smiled and thanked him, then sat on the bed with him and pointed to the strange man. “Who’s this?” I asked.

Stephen looked puzzled. “That’s a man with his head on fire.”

I looked around at the other drawings on the wall: a cow with green stripes, a boy with hands so fat they blotted out the scenery. I thought, Maybe sometimes a man with his head on fire is just a man with his head on fire.

“Are you angry that I left home?”

“No,”Stephen said . “just sad sometimes, but I see you almost every day and Joey says you’re better than his dad because his dad is always working– ”

I hugged him in the middle of this sentence. “Stephen,”I said, “if you feel angry you can tell me.”

“Okay, but I’m not,”Stephen said. “You’re the best daddy in the world.”

I gazed at his mushroom-cut hair, his spindly body, his wet mouth opened in an 0, and at the baby teeth inside, about to make way for grown-up teeth.

“Hey, why can’t I just live here with you?” Stephen asked, his eyes now wide and excited. “We could play catch in the back where all the grass is and you could read to me every night and we could watch Thomas the Tank Engine videos.”

I touched my finger to his lips.

“Why don’t you want me to come here?” he asked, pushing away my hand. “Why don’t you tell Mommy you want me to live with you?”

I stared at him for a moment. If I could pry open the top of his head, would an orange fire leap out and devour us both?

“Stephen,”I said carefully. “You’re the best boy. In the world.”

When Stephen was born, I held him in my hands, out away from my chest, and watched his eyes open and fix on my own. We sat that way for a long time, each refusing to blink. It was then, I believe, holding him and staring into his eyes, Maggie lying exhausted but exhilarated in the hospital bed, that I felt all the love I had inside me pour into him.

Or maybe it was a few weeks later, when I was lying on the couch with him at three in the morning, after the clangy radiator in his room had awakened him from a deep sleep. I shuffled into th e kitchen, holding him in one hand while getting his bottle ready with the other. His cracked screaming in my ear, I plucked the bottle from the hot water, squeezed a drop onto my wrist, arranged him in the crook of my arm, placed the nipple in his mouth, and made my way over to the couch. “You’ re the best boy,” I sang to him. I found an old movie on television as Stephen guzzled the formula, making slurping noises with his lips. As he fell asleep in the middle of it, waking up in time to belch into my face, spit some formula onto my shoulder, and fall asleep again on my chest, a wave of tenderness came over me, and with that wave the certainty that he and I had just sealed something, something permanent, something more solid and unbreakable than a wedding vow.

“It’s so the outfielders know the wall is coming,”I answered, and I was ready to explain how they shoot a quick glance at the wall to locate it while running back, then refocus on the ball in flight and put one hand out to brace themselves for the collision. I was ready to tell Stephen how I had been an outfielder once, and that when I was racing back for a long fly ball I’d feel the crunch one two three and know when the wall was coming. I was ready to tell him how once, at a game where there was no warning track, I had raced back on the grass and crashed into th e fence, hurting my shoulder and missing the ball–And so sometimes, you see, there is no warning– but Stephen was looking up high now and wondering about something else, like why the stadium lights had come on even though the game was over and it wa s still light outside, so I didn’t tell him any of those things.

As we continued down the right-field line toward home plate, I noticed a sign directing Parents and Guardians to pick up your children at home plate. When we reached first base Stephen, with no need for directions, broke away from me, and as he ran I surveyed the other adults, wondering which were the parents and which were the guardians, which were heroes and which were villains. Then I noticed with surprise my dashing son.

At first Stephen had run with his fists closed and his legs windmilling, knees and feet jutting out in all directions as he followed the line of kids in front of him. The rest of the parents and guardians strolled to home plate, looking right and cheering encouragement to their children, while I stood arrested at first base–for just before reaching second, just as Stephen had passed a much taller boy in front of him, a strange thing had happened: his body had begun to collect itself, had come together in flight.

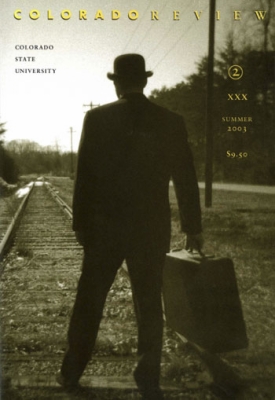

I saw his chin rise, shoulders relax, and fists open as he took the inside corner of the second-base bag with the side of his right foot– Where had he learned that?–and pass two more dashers. Then, between second and third, Stephen accelerated confidently past an entire line of kids–tall kids and short, bad kids and good, kids of all colors, kids with stepdads or stepmoms, kids with single moms or single dads, kids with no parents at all, kids with two parents who hated each other, kids with two parents who loved each other. Stephen exploded past them all, the fire inside now fueling his lithe body. As he rounded third and sailed home, the Mets’ third-base coach smacking him on the ass, Stephen lifted his arms, the gallant victor in the throes of his own grace, and smiled a great smile of triumph, of freedom, of an escape from suffering. And when he alighted in the air above home plate, hovering like a butterfly and landing so deftly it could hardly count as a run, he didn’t seem to notice that his father wasn’t where he was supposed to be. No, he was still standing over by first base, as parents and guardians streamed by him–a man who seemed to have popped up out of nowhere, neither hero nor villain, grinding some warning track dirt in his fist and watching his son from a reasonable distance.