I Used to Be an Athlete

This is mostly about my knees.

They creak now. Stiffen up. When I get up in the morning, I feel like the Tin Man—just a few squirts of WD-40 would really do the trick. I’ve taken to sleeping with a pillow between them when I lie on my side, so I don’t wake up from the pain. You can imagine how sexy that is.

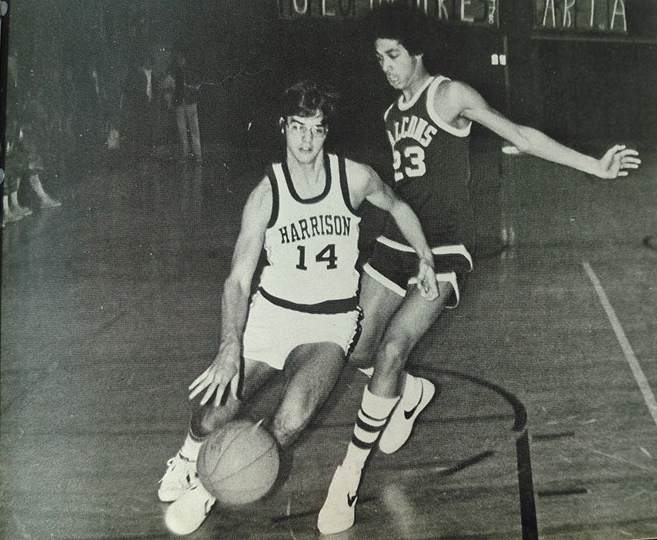

I’m 54. I’ve been an athlete my whole life. It’s half of who I am. (The other half is all geek.) In school I never looked like an athlete (I was skinny and wore thick glasses), but I was the fastest kid at Parsons Elementary (okay tied for fastest, with Ricky Straface), and played baseball, stickball, street hockey, and football at the schoolyard three blocks from my house. In high school I was on the track team and the basketball team, and after graduation I kept on playing basketball for thirty more years.

All the while, without knowing it, I was doing a number on my knees.

It came to a head four years ago. I had been following a particular work-out regiment that involved squats. One day, while out walking with my wife, I felt a sharp pain in my knee and shrieked like a five-year-old. It felt as if my patella had scraped against my femur. I bent over and stared at my knee. What was that?

I walked a little farther and it happened again, just as sharp. And it kept happening until I got home.

When I told my doctor about it and shared my prognosis, he chuckled kindly. “You’re fifty,” he said. “It’s probably arthritis.” And he ordered some x-rays. When I returned a few days later, he showed me the x-rays and pointed out the bone chips that were having a house party in under my knee caps. “Yep,” he said. “Osteoarthritis.”

Arthritis? I kept picturing that commercial showing an old woman wincing as she tries to open a jar.

“Just take a couple of aspirin,” he said. “You’ll be fine.”

Aspirin? Listen, doc. I’m no stranger to pain. I’ve torn ligaments in my ankles over a dozen times, contused my knees, and broken my leg so badly that a surgeon had to bolt the bones together. In fact, just one year before this particular doctor’s appointment I had torn a muscle from my ribcage when rebounding the basketball and holding onto the ball, arms over my head, as a bigger, stronger player from the opposing team tried to rip it out of my hands from behind. (You want to feel pain? Tear a big muscle off your ribcage.)

I understand that arthritis can be very painful, but this thing with my knee felt more like . . . well, you know, an injury.

But I didn’t say anything. I liked and respected my doctor, and I didn’t want to sound like a typical middle-aged man in denial about his aging. But when those sharp, instantly debilitating pains kept coming in my right knee, and then started happening in my left knee as well, I knew it couldn’t be arthritis, so I went to a physical therapy clinic. There, a therapist named Kelly felt around my kneecap for a couple of minutes, bent my knees is all kinds of directions, and said, “Oh, your patella is rubbing against your femur.”

Dear Doc: Told you so.

Kelly explained that all those squats I’d been doing had intensified the tightness of my interlabial band (that thick rope of tissue running down the outside of your thigh—a.k.a. the spot where my father used to punch me when he wanted to give me a “Charlie horse”) to the point where it was pulling my patella off my knee, grinding it into the bone.

“Did you stretch before and after working out?” Kelly asked.

“Stretch?” I said.

Kelly pursed her lips. “Is it possible,” she asked, “that you’ve played sports your whole life but never really stretched that much?”

Why yes, Kelly, that is possible.

What followed was months of intense pain to get rid of my intense pain. (Have you ever rolled the outside of your thigh over a foam roller? It’s like what my Italian grandmother used to do when she made her own pasta.) Lots of physical therapy, and lots of stretching.

And no more basketball, at least for the time being.

This was a challenge. Basketball had always been my life’s pulse. During the sad stretches of my childhood I had found solace in my driveway, shooting hoops day or night, in sunshine, rain, or even snow, usually imagining a Knicks-Sixers game where I played the roles of both Earl the Pearl and Doctor J, the game coming down to the wire and me heaving the game-winner from the sidewalk. I was an okay player in high school, but I got better in my twenties, was actually at my best in my early thirties, missed a lot in my mid-to-late thirties (after my kids were born and my work life intensified), and got back into it in my forties. I’m a college professor, so I was lucky to work at a place where I could go to the gym at any time, and where I could always find a group of men playing “Noonball.” Many of the guys who played were in their twenties or thirties, but some of the men were older than I was, so I saw no reason why I couldn’t, like them, play well into my fifties and even sixties. Hell, one of my friends is in his seventies and has a pacemaker, and he still plays.

So as I was rehabbing my knees with Kelly, I planned on getting back out on the court within a few months. But then, several things happened. Two of my Noonball pals, both younger than I am, injured their knees (one his ACL, the other his meniscus). And my older brother, who played far more often (and much better) than I ever did, told me he had quit. Meanwhile, it was taking an awfully long time for my knees to get better, even with the PT and the stretching. All of these, to me, were warning signs: Quit while you’re ahead. Quit now because what happens next may be worse than a sprained ankle or a painful knee.

So I did. When my knees recovered, I didn’t go back. But then I injured myself anyway while running on a treadmill: torn meniscus. And then, after that knee healed, I tore my other meniscus, popping it while goofing around with my dog outside.

So now I had a new problem: I had gone directly from being a he’s-still-got-it 50 year-old to a hobbling old fool who couldn’t even walk very well. And then, even after my knees healed, I had an even worse problem: I was fat and out of shape. And I had become a complete wimp: a middle-aged man who occasionally rode his bike to work and considered walking the dog my exercise for the day.

And that’s where I am today. I am tempted—constantly—to return to the gym, lace up my high-tops, and play a little five-on-five. But at the same time, I’m wary.

Enter my wife: “Why not just join one of those over-50 leagues? You could still play, but, you know, take it easy.”

I smile and nod. “Great idea.” She’s so sweet, isn’t she? The Over-50 League! You might as well tell me to play shuffleboard.

Which brings up another problem: I’ve never known how to “take it easy.” I’m too competitive. I simply can’t turn down the volume. I tell myself to let the youngsters do all the rebounding, to stay out on the perimeter and stop driving to the basket, but then I end up diving on the floor for loose balls, scraping and clawing for rebounding position, fighting through picks to stay on my man. The Over-50 league? No thank you.

No, I think I need another sport. A “transition” sport.

And by “transition” I mean from middle-age to death.

How about golf? I hear you asking. You know, the kind of sport people can play even when they’re . . . older.

Someday, perhaps. But not yet. Right now, I’m still in limbo: unwilling to admit I’ve actually given up the team sport I love, and unready to head over to the Active Adult Center (conveniently located five blocks from my house) for Senior Yoga.

What about swimming? That’s the best kind of exercise.

Swimming? Just shoot me. The very idea of swimming laps, back and forth, without ever racing someone or scoring any points or trying to win something, makes me physically ill. Plus, you really don’t want to see me in a Speedo.

Look, I don’t expect anyone to understand this, but I need an activity where I can occasionally kick someone’s ass, or wallow for days over failing to kick someone’s ass.

(In other words, I am not the nice person you may think I am.)

Tennis? Squash? How about racquetball?

My knees hurt just thinking about those. Plus, there’s just something I love about team sports. I need to feel that camaraderie among my teammates, high-fiving one another when things go well, and patting one another on the back when they don’t.

Why team sports? And whence this fierce need to compete?

Excellent questions.

It may have something to do with my childhood. (Doesn’t everything?) When I was a boy, my sister died suddenly, and my family changed before my eyes. In the years that followed I found great comfort at the schoolyard, in the gym, and in my driveway. Life, to me, had been a loss. But out there, I could win. At home, I could never make things right—as good a kid as I was, I couldn’t possibly compensate for the death of my sister. Out there, I could deliver a deft pass for an assist, hit a sacrifice fly to bring the runner home, or shut down the other team’s leading scorer. I could make a notable contribution. It was even possible that I could save the day.

Possible—but as things turned out, not likely. Except for a clutch assist or two, or a few gold medals at local relays, more often than not I fell short. The remarkable thing about athletics is that 99% of all participants end their season in disappointment and spend the entire off-season focusing on what they could have done better.

But now, in retrospect, I can see that it was not necessarily the succeeding but the competing, the striving, that’s always mattered to me, the understanding that I could do better next time; I could always improve. There was always the next shot, the next game, the next year.

Until there wasn’t.

Which brings me back to my knees.

I’m tempted to tag on something uplifting here, something folksy: So now I’ll be content to join Wednesday Night Volleyball at the Rec Center and take brisk walks with my wife and appreciate that I’m alive and healthy and my goodness, can you imagine the kind of pain real athletes go through when they age? And believe me, it’s true. I am grateful to be alive. I’m grateful to be healthy. Every day, I wake up with a beautiful woman and feel thankful that she’s still with me. I feel grateful that my kids are doing well and that I have a good job and a good life.

And then I get out of bed and my knees are on fire.

So the truth is, I’m outwardly grateful, but secretly pissed. Pissed that I can’t run around and play anymore. Pissed that I can’t combine all the knowledge of basketball I’ve gained over the decades with the body I had when I was 25. Pissed that when I was at my basketball best, I was working three jobs and hardly ever set foot in the gym. Pissed that I didn’t realize it was all going to be so fleeting.

Life, that is.

So there will be no positive spin here at the end, because even though I can be upbeat in my life, in my writing I try to tell the truth. And the truth is, it sucks when your body wears out on you.

So now, I will walk a lot. I will ride my bike. And I will probably take up tennis or golf. But I will forever miss the brotherhood, the “team-ness,” of basketball. This may have something to do with the fact that my siblings and I haven’t had consistent “team-ness” in our own lives (due first to my sister’s death, then our departures for college, then my move to Colorado, far away from my family in New York), and that’s what I’ve loved most about sports. Because that “team-ness” is magical. It doesn’t always happen, but when it does, there’s a cosmic uplift, an elevation of mood and energy—disparate selves made whole through the web-like connectivity of a shared enterprise: five guys on the court, unconsciously knowing everything about one another. When a team “clicks” like that (the way the Seattle Seahawks defense did throughout the playoffs last year, and the way the San Antonio Spurs always seem to do), that’s when you see players smiling and hugging and chest-bumping, not just because they are winning, but because they’re bonding, they’re feeding each other, they are performing at their athletic best and acting somehow as a unit. In spite of all the petty rivalries and locker-room belittlements and jealousies over playing time and bitterness towards the coaches and hatred of opposing players and macho chest-puffing and trash-talking, they have all managed together to elevate their game and create a feeling of camaraderie, of mutual respect and admiration, of love.

Just like a family.

Or the way a family is supposed to be, anyway.

So I guess when I say I miss playing sports, team sports, I’m saying I miss the brotherhood of the game. I miss my brothers on the court. I’m saying I miss my own brother and my own sisters. I miss the way my family used to be, way back when.

And I’ll never get that back.

What a wonderful essay, David. I found it insightful the whole way through, but it’s the ending that really knocked me out. Wishing you could come play in my Sunday b-ball game this afternoon–but I’ll settle for a round of golf (team golf?) one of these days.

Thanks, Jimbo!

You were a great basketball player. We had great times playing together.

Your father was a great coach at St Gregs.

Ricky! I’m sorry I missed this. I definitely was NOT a great player, but I had fun, especially when playing with you. (Remember your half-court shot that won the game? Legendary!) But yes my dad was a great coach, I’ll agree with you on that. Great to hear from you, buddy. — Dave

This is funny. I just read an old article of yours about Creede, which I loved, and found this after I searched your name online. What a gifted writer. At 65 I just had to give up playing ice hockey with the 20-30 year olds and I’m devastated. I wanted to play until 70 but my chronic a fib finally won out. Your article helped me realize why I wanted to hang on so desperately. It’s the guys. 20 year olds who look up to me because I played college hockey and could still play with kids half my age. The beers in the locker room after the game where they would ask my advice about working…or politics. I miss it. Thanks for sharing. I need to find your novel now.

Thanks, John! I feel your pain. (Literally. In my knees.) I’m still at a loss about what to do for exercise that will come close to matching the competitive joy I felt when playing hoops. Ack. Maybe if you coached ice hockey?

Anyway, if you want to stay in touch, my email is david @ david-hicks.com