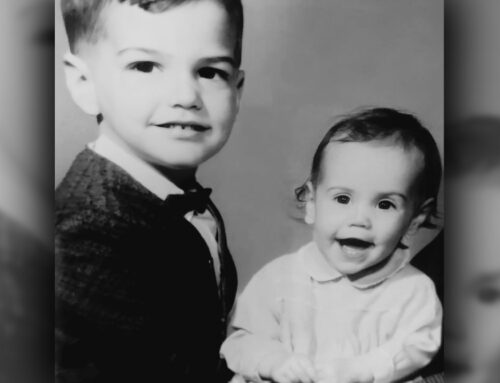

Unknown Man

When my son Stephen was eight years old and we lived in the Pennsylvania woods, he occasionally donned a makeshift red mask, cloaked himself in a red cape (from an old magician’s costume), and stood in the corner of a room, perfectly still, willing himself to be invisible. Then, when one of us passed by, he would leap out from the shadows and fling his weapon at us.

He was Unknown Man.

He employed a variety of weapons with which to slay villains—an old film canister filled with thumbtacks, another filled with dust (to dash in the their faces, blinding them), a long string with a grappling hook—but his favorite was a stack of disks,actually soup-can lids, that, when flung properly, could decapitate a 300-pound man, to say nothing of the many villains inhabiting the Pennsylvania woods.

He’d leap out from his hiding spot like a man with his head on fire, flinging a death-disk. His enemies, cleverly disguised as pine trees, were instantly vanquished. Then he’d laugh triumphantly, retrieve his weapon, wrap himself in the cape, and dash off (invisibly, of course) to his next mission.

One summer afternoon, I was making dinner in the kitchen, and my daughter Caitlin, who was four, was bouncing barefoot on the downstairs couch. Suddenly, Unknown Man leaped out from the shadows and flung his death-disks “at” her. (Really he aimed at the wall behind her–Unknown Man was all about the element of surprise, not actually hurting anyone.) Caitlin, who had been laughing–she loved it whenever Steve paid attention to her–suddenly looked down and grabbed her foot. Blood was oozing from her toe.

Stephen had wrapped most of the aluminum lids in duct tape, but some of the tape must have peeled off this one.

I hustled over, trying to remember if Caitlin had gotten a booster for tetanus. I imagined my daughter living without a big toe for the rest of her life. I had just moved to Pennsylvania and didn’t even know where the nearest hospital was. Ice, I thought—I should pack the sliced-off part of her toe in ice.

But when I got to her, I could see that the cut wasn’t too deep. She was looking around for Unknown Man, but he had disappeared. She frowned. My brother, my assassin.

I wiped the blood, inspected her toe, and worried. What would have happened if it had sliced her eye? Her face? Her jugular? I’m sure I had told him never to fling any death-disks at his sister. That would have been a fatherly thing to say, right?

I cleaned Caitlin’s wound, wrapped it in gauze, and elevated her injured foot. Then I went outside, looking for Stephen. I was ready to ask him how he’d feel if he cut open his sister’s face. I was ready to slice his own toe and say, There, how does that feel? But I found him outside, hiding behind a tree, crying.

I didn’t mean it. I was aiming for the wall. Is she okay?

I might have yelled at him. I probably just gave him a hug, told him to be careful around his sister, and so on. Who knows. But it was all okay; it was just an accident. For a kid whose father left when he was young, he was bound to have anger issues, and maybe (I feared) he would end up taking out his anger on his sister instead of on me–in the form of an “errant” death-disk, for example. But this seemed like a genuine accident, and the important thing was that Cait was all right, and we were all together, after having been apart for a long time, and we were happy, we were in a magical place during what, in retrospect, was a magical time. A time when we had no functioning television and a lot of woods to play in. A time when Cynthia and Caitlin made cakes and painted pictures, when Steve and I played catch outside, and when the kids used their imagination for entertainment–for hours. A time when high-tech games meant playing Sorry or Monopoly. A time when we’d sit out back and wait for the flying squirrels to launch, then watch for the blue heron swooping down the creek, looking for fish. A time when we’d walk down the pitch-black road at night, look up at all the stars, and tell “myth stories” about the constellations. A time when they opened their own “shops” and sold items (drawings, poems, chores like washing windows or taking out the garbage) to their “customers,” meaning Cynthia and me. A time when we read books, and when Caitlin would take a half hour recounting the plot of the one she had just read, and I’d get caught up in the sound of her voice, telling a story.

I relished it. I’m telling you, none of it was lost on me. I savored every minute of their imaginative, creative selves, these beautiful children of mine, unaware (and yet on some level completely aware) that in a few short years technology would take over our lives, that they would be going through the Emotional Hell that is Puberty, that I would be writing about these days on something call a “blog.” All I knew then was that I had my children with me, I had a wonderful woman in my life, and I lived in a magical place. As for everything else, I had no idea what I was doing. I didn’t know who I was, who I was going to be, what I wanted to do for a living. It wasn’t a mid-life crisis; it was a mid-life reboot.

I was Unknown Man.

By donning the mask and cape, Stephen was unconsciously representing me. For over a year, he hadn’t seen much of me. To him, I was a voice on the phone, an image on a video, handwriting on a card. Not death-disks, to be sure, but weapons of sorts, intended as acts of kindness–sharp reminders of my absence. The man he knew as his father was someone who lurked in the proverbial shadows, but who might someday (you never know) materialize out of nowhere to save the day.

Like some invisible superhero.